The mountain of paperwork I had to fill out before I received the contract for my most recent job in Japan. Yup, all in Japanese legalese!

Who would have thought it? Crappy bureaucracies exist everywhere, and just when you think you’ve experienced the worst, another one pops up behind you, taps you on the shoulder, and then hands you a bunch of forms in legalese to fill in.

Japan was a country that made me appreciate Centrelink, an Australian bureau of welfare services. I had tried to register with Centrelink several times when I was a university student and had encountered a wealth of paperwork and sometimes illogical-seeming red tape to get the services I wanted. Although I understood the logic behind the system to some degree, at the time I was flabbergasted at how hard it was for disadvantaged or needy people to get help.

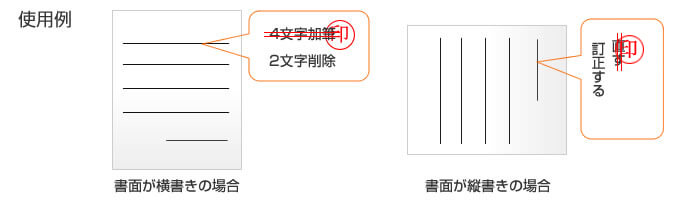

In Japan I encountered similar problems. To list an example, I’m wont to make mistakes when filling out forms, but unfortunately for me, if you make mistakes filling out a form in Japan you have no choice but to write it again unless you have a stamp of your name (inkan or 印鑑) to plant over the top of the errors:

Diagram on how to correct mistakes in Japanese forms. The name stamp is the red circle.

I remember being reduced to tears when I first applied for a postal savings account in Japan, being handed my third registration form to fill in with complicated Japanese characters after yet another mini-mistake in my kanji strokes on one word. Thankfully now I have a name stamp of my own, but rue the days that I forget to bring it with me and have an unexpected form to fill in! Depending on the institution and the person who serves you, signing with your signature instead may or may not be an option, but it tends to be better not to count on it.

Another example is the inconsistency with processing non-Japanese names within the system, which admittedly is largely due to the comparatively insignificant (yet growing) number of foreign residents without kanji for their names. Some places require you to register with your name in katakana Japanese phonetic script, while others will let you write in romaji, Roman characters. Some places have set requirements for how you order your name (i.e. surname first, first name second and middle name/s last, etc.) and others aren’t so fussy.

e.g.

False Name McGee

McGee, False Name

マクギー ファルス ネーム

マクギー F.

etc.

While initially this may not seem like much of a problem, when you then sign up to other services, depending on the service you may need to write your name as per a particular document! I discovered this when I accidentally wrote my name for (I think it was) my postal savings account differently to what was written for my Alien Registration Card or 外国人登録証明書 (as it was then known), as only one of them included my middle name. A further document, I believe it was my health insurance card, was written in katakana. From that day on, whenever I had to sign for or apply for something, I had to resubmit form after form when it was discovered that the name I had to use in the form had to be exactly the same as my postal savings account. Or my Alien Registration Card. Or my health insurance card. Writing my name differently on different cards made it a nightmare to write my name – on the face of it one of the few things that you never get wrong on a form – from then on!

My point is, Japan tends to be a stickler for the rules when it comes to paperwork and procedure, in the office, in the government – hell, in everyday life! This is something which has bothered me, a complete wreck when it comes to bureaucracy in any language (as the above examples show), to no end.

On that positive note, I’m looking forward to sharing with you two of the adventures I’ve had with the system in Buenos Aires so far! To my complete and utter surprise I think it might be a more extreme bureaucracy than Japan… Stay tuned!